In my teaching, I seek to help students to connect their enthusiasm and curiosity for a particular time and place to an exploration of broader historical issues, as they learn to build coherent arguments that are well supported by evidence. I make use of three main methods to reach this fundamental goal: 1) a focus on intensive discussion and cumulative writing projects that foster critical thinking; 2) the utilization of a multidisciplinary approach that engages students through a variety of interpretive perspectives; and 3) an emphasis on working with primary sources and making informed use of the latest technological resources, drawing especially upon the Digital Humanities.

By focusing on intensive discussion and cumulative writing projects, I invite students to develop their critical thinking skills in analyzing historical issues and articulating that analysis to others. One of the ways I do this is to ask them to “be” medieval university students for a day in my classes here at the University of North Texas: HIST 4218: Early Medieval Europe and HIST 4219: Late Medieval Europe. Four or five times during the semester, all students take part in a modified form of medieval debate: the disputatio. In the Middle Ages, university masters would read to students from texts such as the Bible, Augustine, or Gratian for four days a week. On the fifth day, students had the chance to debate a question posed by the master and develop arguments supported by logic and evidence. In our modern version, all students arrive on a disputatio day having prepared at least two different written arguments, backed by evidence, in response to a debate question such as, “Are historians ever justified in using the term the ‘Dark Ages’?” Then, six students align themselves along opposite sides of the debate and orally present one of their arguments to their fellow classmates. Following the presentations, the debate is opened to the class in general, wherein each student in the audience must pose at least one question to a presenter and critique his or her argument. Disputationes are designed to encourage students to synthesize sources and evidence; to learn both to pose and to answer critical questions; and to promote the idea that good historical questions often do not allow us easy yes-or-no answers.

I have also sought to supplement traditional historical inquiry with a variety of aesthetic and experiential perspectives via a multidisciplinary approach that employs elements of the visual and performing arts. While at Oxford, I worked with composer Jonathan Williams and the student vocal music ensemble, Consort Iridiana, to bring Felix Fabri’s fifteenth-century “imagined pilgrimage” to life through live music, text, and image. In 2018, as an Invited Research Collaborator with the Leverhulme International Research Network Award project, “Pilgrim Libraries: Books and Reading on the Medieval Routes to Rome and Jerusalem,” I refashioned the Consort Iridiana project into a short video that I share with my current students: “A Virtual Pilgrimage: Felix Fabri’s ‘Sionpilger’ and the Unicorn” (2018, runtime: 10.14min). I have put this multidisciplinary approach into regular practice within my classes, as well. For example, analysis of visual sources (such as Ice Age paintings in the Chauvet Cave, France) and an introduction to music produced during the eras we study (such as Minnesinger songs promoting Crusade) are part of every class session that I teach. In the History of the Book seminar and hands-on workshop I developed at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA)—and which I intend to offer at the University of North Texas—students in this course produce both analytic writing projects and hand-crafted creative pieces prompted by a central course theme question: “How does technology influence the way we write and think?” The variety of their responses—from digital “non-linear” narratives; to a hand-inked papyrus; to a book of science fiction poetry illuminated in a traditional medieval way—can be seen in their online exhibition, History of the Book @ UTA.

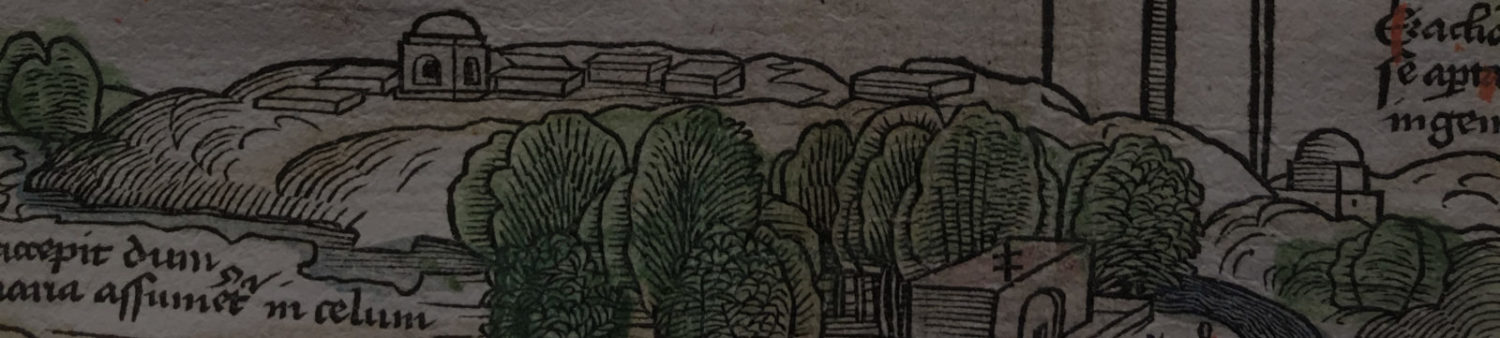

Finally, in placing an emphasis on working with primary sources, and with thoughtful use of the latest technology, I encourage students to act as scholars in their own right, not simply to be recipients of established knowledge. For example, in my HIST 4331: Medieval Travelers class taught at UTA (and that I am currently teaching at UNT in fall 2019), I assigned students to find digitized primary source material on the internet relating to medieval travel. We then compared the students’ findings to actual primary source materials in two trips to the UTA Central Library’s Special Collections. During these sessions, they compared online sources, such as the Bodleian Library’s digital exhibition of the tenth-century Islamic “Book of Curiosities” with late-medieval maps and an actual page of the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle held at UTA. Finally, each student produced a blog post detailing his or her analysis of a chosen primary source for the class blog, Medieval Travelers. Thus, they not only received an introduction to incorporating primary sources into their research, but they also learned to handle a five-hundred-year-old map page safely. Moreover, they analyzed its construction as a material object and traced patterns of similarity and difference in medieval and early modern maps. At UNT, students in HIST 4260: Medieval Travelers students will take the assignment one step further and provide audio podcasts to showcase their primary source analysis. Introducing students to the latest digital technologies is also important to my approach.  For example, my HIST 3302: Medieval Technology and Scientific Thought course at UTA included a cumulative, semester-long project in which students used the digital facilities of the FabLab, UTA’s maker space, to craft at least one part of their entry into the final class team “siege engine competition.” Videos of the final products (yes — catapults and ballistae!), including discussion of the digital elements, can be seen at https://youtu.be/SqExq4oX9AI and https://youtu.be/UlAQqwkvTqc. This course also partnered with the UTA Libraries’ Maker Literacies Initiative. By using both primary and secondary material at hand, online, and in digital-rich maker spaces, I seek to employ the best of the growing field of the Digital Humanities to enhance my teaching.

For example, my HIST 3302: Medieval Technology and Scientific Thought course at UTA included a cumulative, semester-long project in which students used the digital facilities of the FabLab, UTA’s maker space, to craft at least one part of their entry into the final class team “siege engine competition.” Videos of the final products (yes — catapults and ballistae!), including discussion of the digital elements, can be seen at https://youtu.be/SqExq4oX9AI and https://youtu.be/UlAQqwkvTqc. This course also partnered with the UTA Libraries’ Maker Literacies Initiative. By using both primary and secondary material at hand, online, and in digital-rich maker spaces, I seek to employ the best of the growing field of the Digital Humanities to enhance my teaching.

My three main teaching methods—a focus on intensive discussion and writing; a multidisciplinary approach; and an emphasis on primary sources and informed use of digital technologies—together underpin my fundamental goal in the classroom: to connect student enthusiasm with a broad historical understanding and the ability to make and evaluate arguments. These methods and goal arise from my experiences of the liberal-arts Socratic tradition; the rigor of the debate-intensive Oxford tutorial system; and the discussion-rich classes of the American state university. The positive student feedback that I have received over the years, as well as the two teaching awards that I received in 2017—the UTA College of Liberal Arts Dean’s Accolade Award, and the UTA College of Liberal Arts Teaching Award for Tenure-Track Faculty—indicate that that my teaching methods are effective and well received. Nevertheless, seeking new ways of synthesizing these approaches and continually endeavoring to improve my teaching constitute for me an important, and lifetime, project.